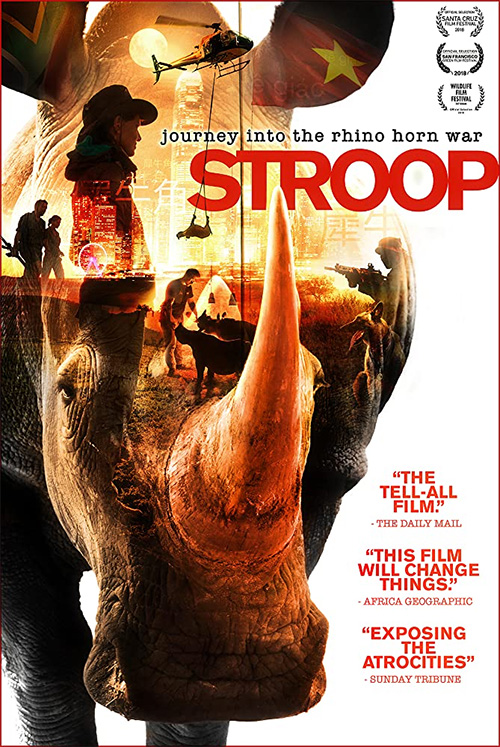

STROOP: Journey into the Rhino Horn War

By Susan Scott

Photo: STROOP Journey into the Rhino Horn War

A hundred years ago there were one million rhinos worldwide. Today only 29,000 remain.

Every 8 hours of your life one rhino is slaughtered.

A Kruger National Park ranger is 12 times more likely to die in the line of duty than an FBI agent.

Wildlife trafficking is the 4th most profitable illegal trade after drugs, guns and humans. The trade is worth twenty-nine billion US dollars annually.

These shocking statistics are just part of the stark reality of this Journey into the Rhino Horn War. I am sure that many people, even those with only a passing interest in the natural world, will have some awareness of the current scourge of wildlife poaching and that black and white rhinos in Africa are at the forefront of this cruel trade due to the value of their horns. But STROOP delves deep into the complexities of this transnational organised crime and provides us with what is probably the most comprehensive account of the various pieces of the jigsaw so far.

It isn’t an easy story to tell and there are plenty of distressing and painful scenes emphasising the immense cruelty that underpins the trade. It is clear that at its most basic level this is an animal welfare tragedy as well as a conservation one. The physical and psychological distress that targeted rhinos and their calves undergo is apparent throughout. In the opening scene Axel Tarifa recounts the traumatic experience of poachers raiding the rehabilitation centre for orphaned rhinos where he worked in South Africa – even tiny adolescent rhino horns have become a target. Despite the harrowing scenes, the director and narrator Susan Scott, manages to sensitively capture the emotion and still maintain a level of objectivity necessary for a documentary.

The list of players on both sides of the rhino war is extensive. STROOP manages to find ways to access most of them whether it is rangers protecting the animals in South Africa (where the largest population of rhinos live) to consumers in East Asia convinced that their horn purchases will have medicinal benefit. What stands out about this documentary is that the less visible players are also included. That covers political corruption in South Africa; the inadequacies of CITES, the multinational treaty designed to control the trade in wild fauna and flora; the local court system in South Africa where the poachers are tried; the African communities that the criminal syndicates target to recruit their poachers; the manifestation of a growing middle class market in rhino horn jewellery as a status symbol not just for traditional medicine in China, Vietnam and Hong Kong; and the water muddying issue of rhino farming in South Africa and their lobbying for a legal market for the horn.

The complexity of the rhino horn war and its many actors makes for a documentary that jumps around from country to country and player to player. STROOP manages to bridge the leaps fairly well without breaking the flow of the film. However, it does inevitably make for a long documentary at 133 minutes. The length is a shame because, on a practical level, that makes it less attractive as a tool for activists and campaigners to raise public awareness with.

I would certainly have liked to see more of an in-depth critique of rhino farming and its trade in South Africa. Although that could fill a documentary on its own and is probably best tackled under the wider question of the ethics of wildlife farming in general. Likewise I would have liked to see further discussion on the South African communities involved in the poaching and exploited by the traffickers, how the social, political and economic inadequacies are part of the root problem and what can be done to mitigate that.

Earlier this year I was slowly driving along a remote dirt road in Kruger National Park close to the Mozambique border where many poaching teams enter from. I hadn’t seen a soul for a couple of hours until I spotted something that looked like people out in the bush. Through my binoculars I could see that it was two foot rangers sitting with their weapons propped up beside them under an acacia tree in the mid-day sun. I couldn’t see the rhinos that they were no doubt assigned to protect but the feeling of security that their presence gave filled me with warmth and gratitude. These guys literally risk their lives for some of the world’s last remaining megafauna and if nothing else STROOP strips bare the local and international realities of their story and explains to us why they have to do it.