If you’ve walked on a beach during the summer or stood on a pier looking into the ocean, the chances are that you will have seen them....

As an ORCA Wildlife Officer I used to use them as a tool to get children interested before a ship had even left the harbour. They float mysteriously below the side of the ferry in a plethoraof shapes and colours: an exotic and magical creature hinting at the strange and wonderful world that exists beneath the waves. They are jellyfish. And in recent years we have seen huge numbers of these incredible invertebrates in our waters. Every summer, a different sensational round of news stories emerges about them; whether it is an invasion of them on our beaches, or the dangers of being stung by jellyfish. Last year itwas the gigantic size of a barrel jellyfish that UK television wildlife presenter Lizzie Daly was photographed scuba diving next to in Cornwall. The jelly was so large that it dwarfed her and her fellow diver!

Photo: Moon jelly fish, Iceland

Actually these creatures are nothing new and have populated our oceans for millions of years. Although interestingly, because they are gelatinous and have no bony structure, they are not common in the fossil records. A seemingly basic but really rather complex life form, some propel themselves through the water by their umbrella shaped bells. Some, like the lions mane jellyfish which we regularly see in UK waters have long stinging tentacles that are used to disarm their prey. Others like the moon jelly simply look like pulsating disks floating in the water column. They are part of the plankton biomass. Plankton derives from the Greek word planktos, meaning wandering or drifting. Most jellies are immobile and reliant on wind and currents, a few species have limited propulsion. As a result they can be prone to swarming in large blooms and stranding on our beaches in their thousands. The next couple of months are the time of the year when we are likely to experience jellyfish swarms on our coasts here in the UK.

Photo: Barrel jellyfish, Hebrides

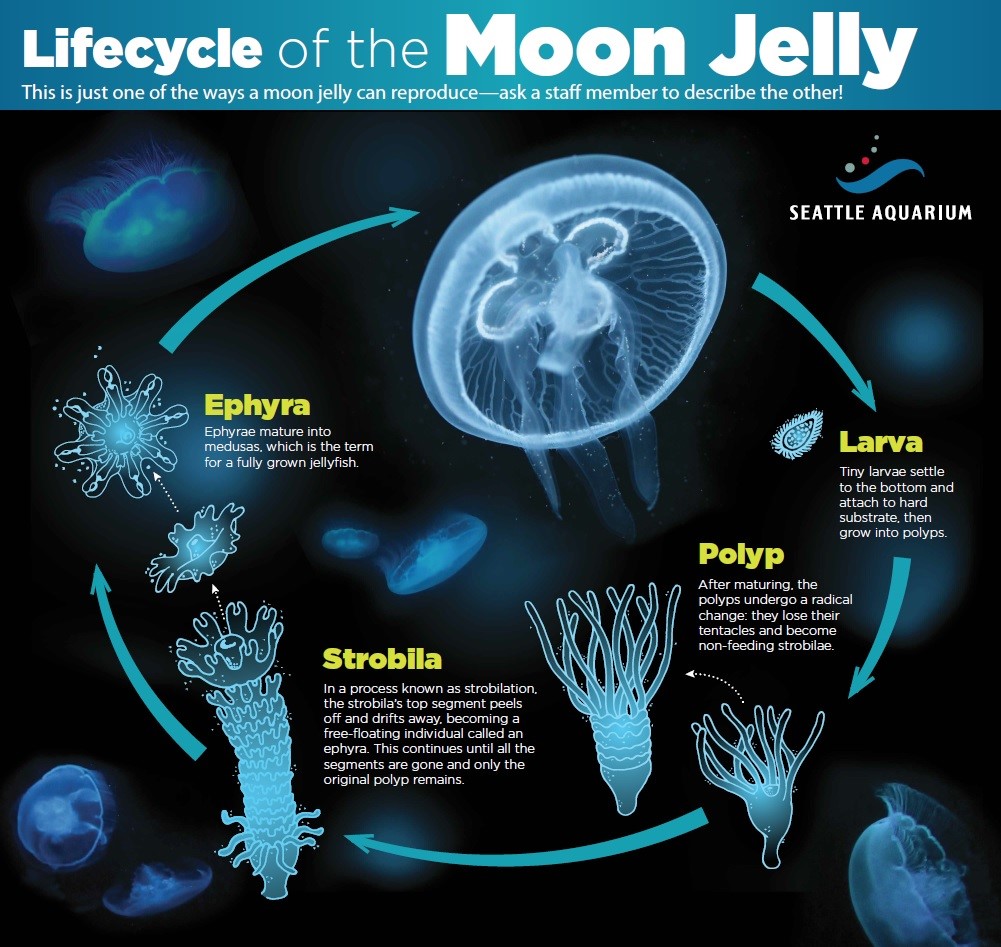

The moon jellyfish is one of the most common species around the UK. It has a fascinating lifecycle and the jelly form is just one part (the medusa stage) of it’s cycle. In it’s juvenile form it is sessile; an immobile polyp attached to a substrate on the seafloor where it grows into its medusa stage before drifting off into the top of the water column where we tend to encounter it.

Children are always intrigued to learn that jellyfish don’t have bones, heart or brain, and that their mouth and anus are one and the same and that they can’t actually see. They are, however, particularly efficient feeders and take advantage of some of the many problems that our ocean ecosystems face. Many jelly species seem able to cope with the rising temperatures that global warming brings and can exist in less oxygenated and more acidic waters caused by carbon emissions, agricultural run off and human waste. Overfishing of small fish such as sandeels and anchovies results in less competition for the zooplankton which they both feed on. Conversely the removal of the numbers of their predators higher up the trophic scale, such as turtles and tuna, has also probably contributed to jellyfish proliferation.

It is the link to these predators that also excites me during the summer months. Two particular species return to our waters to feast on our productive plankton resources. Both ocean sunfish and leatherback turtles are large and impressive marine megafauna. Both species, but particularly leatherbacks, are very partial to jellies! I shall be keeping my eyes out for them!

(This article was adapted from a blog written for the conservation charity ORCA whilst I was working for them in the Hebrides.)